Stephen Mortlock casts on eye to the past and documents the agrarian, tribal existence that followed the fall of the Roman empire.

Under constant attack from barbarian tribes, the Romans had been forced to recall their armies from Western Europe to defend Rome. As the Romans left, many of their practices fell into disuse – the Roman Empire had come to an end. People in Europe returned to a more tribal, agrarian existence and the Romans knowledge of public health declined. Europe was entering the “Dark Ages, or Early Middle Ages”.

This period, from about 400–1000 AD, when there was no Roman emperor in the West, was marked by an economic and scientific deterioration in Western Europe with frequent warfare and a virtual disappearance of urban life. England became divided into seven self-ruled kingdoms, Kent, Sussex, Wessex, Essex, East Anglia, West Anglia (or Mercia) and Northumbria.

By the end of the 5th century, London was largely an uninhabited ruin. And it was not until 871 AD that Alfred the Great became the first king to rule all of England returning to London (circa 886) to make it habitable once more. Although, progress was stagnating to a certain extent during this period, there were still some great minds exploring the universe and trying to find answers. In Europe, although many books had been destroyed or scattered throughout the land, Irish monks were producing beautiful, vibrant illuminated manuscripts. In England, the Venerable Bede (672- 735 AD) was meticulously recording the Saxon Era during a time of raids from the fierce Northmen, bringing terror with their dragon-boats.

Rudimentary care

The Northmen have long been thought of as fierce, uncouth barbarians, but their famous longboats were marvellous feats of engineering, hundreds of years ahead of their time. The Vikings and the Saxons were capable of exquisite metalwork and metallurgy, with the fine swords and beautiful jewellery found in sites such as Sutton Hoo (in Suffolk) and Ladbyskibet (in Denmark) showing that, even if the progress of empirical and observational science was slowed, craftsmen still pushed boundaries and tried new techniques. In this, they were undoubtedly influenced by ideas that filtered up the trade routes from Greece, Egypt, and even China and India.

But, the study and practice of medicine went into deep decline and although medical services were provided, especially for the poor, in the thousands of monastic hospitals that sprang up across Europe, the care was rudimentary and mainly palliative. People died from simple injuries and wounds, while the rough wool clothes worn by peasants led to numerous and widespread skin diseases. Scarcity of fruits, vegetables and proteins needed for a healthy diet led to maladies of the intestinal tract and scurvy. Winter was especially hard on medieval society, as cold, draughty dwellings would have led to numerous cases of pneumonia. Poor sanitation made typhoid a constant problem, especially in the warmer summer months. It has also been speculated that “spring fever” (lecten adl) found in the Anglo-Saxon leechbooks (Old English word lǣce-bōc, or book of medical prescriptions) is the spring manifestation of tertian malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax. It went by a variety of terms the most universal being “ague”, meaning the shakes, and sometimes “fever and ague” referring to the cyclic breaking of a fever.

Diseases

In post-Roman England earthen floored, open-structured wooden homes with thatched roofs would be an ideal way to concentrate malaria in a thinly populated marshland area. There is archaeological evidence and contemporary records that show the spread of tuberculosis and leprosy throughout Europe during this time. It is now believed that leprosy had entered England by the 4th century, possibly with the Romans, and was a regular feature of life by 1050, it remained the most feared disease of the Middle Ages, until the Black Death, started spreading across Western Europe. Not forgetting the other diseases – smallpox, diphtheria, and measles.

People believed that all disease was either punishment for sin or the result of witchcraft or possession. However, the Holy Roman Emperor Charlamagne (742 -814 AD) decreed that each cathedral and monastery should have a hospital attached to it and establish a school where medicine could be taught. Inside the abbeys monastic medicine flourished, which in some regions often represented the main reference point for health care for all residents (common people, nobles or clergy) during this time.

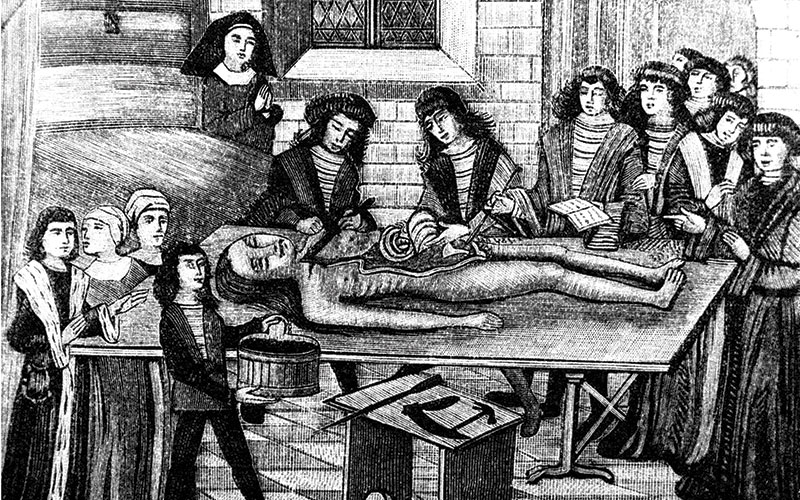

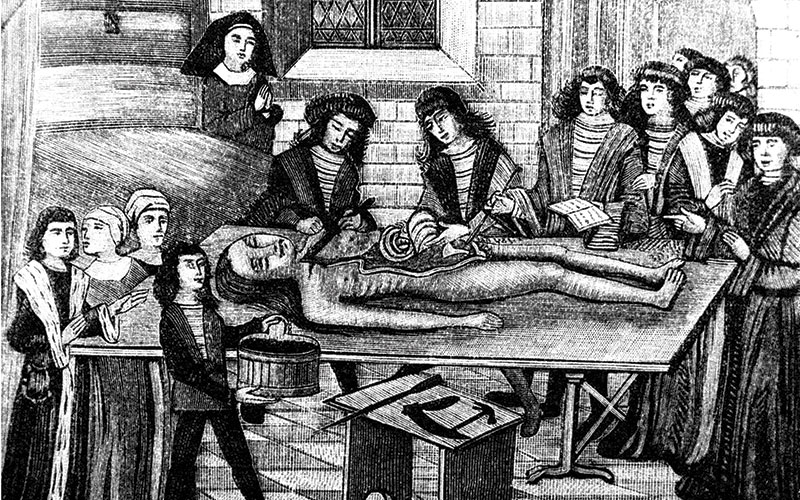

A rudimentary practice of surgery (“touching and cutting”) at the monastic infirmary was usually linked to the management of trauma, including lacerations, dislocations, and fractures. Complicated wounds or injuries may have forced some monks, “the infirmarians”, to request the services of more experienced local bonesetters or even barber surgeons.

Other popular healing practices of the Middle Ages that were integrated into the monastic medical routine, including bathing (not otherwise common), preventive bloodletting, and diagnostic examination of pulse, stool, blood and urine. By 900 AD, Isaac Judaeus, a Jewish physician and philosopher, had devised guidelines for the use of urine as a diagnostic aid and the urine flask became the emblem of medieval medicine. Monks remained with the sick and dying patient throughout the day and night, praying and reading from the Scriptures by candlelight. The point of this vigil was to ensure “proper passing”; on the premises that nobody should be left to die alone. Many monks paid with their own lives when treating the sick.

Plants and herbs

No monastery would have been complete without a medicinal plant garden and a farm, the monks performed extensive land reclamation to create suitable farmland by a progressive control of seasonal flooding of rivers and basins. The plants and herbs they grew were used to treat their patients and much of the information about herbal medicine and related medicinal substances came from De Materia Medica an encyclopedia written by Dioscorides, the Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist, this was widely read for more than 1,500 years. Some plants were used for specific disorders, while others were credited with curing multiple diseases. In many cases, draughts were made up of many different herbs. Medieval medicine was based on the four humeral theories notion of Hippocrates and Galen.

The four “humours” were related to the four elements: blood (air) was hot and moist, phlegm (water) was cold and moist, yellow bile (fire) was hot and dry and black bile (earth) was cold and dry. It was the physician’s job to work out how to restore the balance of a person’s humours if they became ill, and so plants and herbs were ascribed properties to redress the balance.

A cooling herb would be used if you were considered to have too much blood or yellow bile. Sage (Salvia officinalis the name comes from the Latin salveo, meaning “I am well”) was used by the Romans in medicine and cooking. In the medieval period, sage was described as being “fresh and green to cleanse the body of venom and pestilence”. It was also chewed to whiten teeth and used very frequently in cooking along with lots of onions and garlic. So the sage and onion stuffing with the Sunday roast has a medieval pedigree.

Camomile (Chamaemelum nobile) flowers are good for making sedative and digestive infusions that also combat flatulence. Chamomile tea with dittany (Dictamnus albus), scabious (the common name “scabious” comes from the herb’s traditional usage as a folk medicine to treat scabies) and pennyroyal was a preferred medieval remedy against poison. Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) was often referred to as “Boneset” and grown in infirmary gardens for its power to heal wounds and inflammations and (as its nickname suggests) help to set broken bones.

One cure for headache was to bind a stalk of crosswort (Rubiaecae family) to the head with a red cloth. Chilblains were treated with a mix of eggs, wine, and fennel root. Agrimony was cited as a cure for male impotence – when boiled in milk, it could excite a man who was “insufficiently virile;” but when boiled in Welsh beer it would have the opposite effect.

Asian spices

It should be remembered that Asian Spices in Europe were costly and mainly used by the wealthy. A pound of saffron could cost the same as a horse, while a pound of ginger as much as a sheep. It was Charlemagne who encouraged farmers across Europe to plant an abundance of culinary herbs (eg. anise, fennel, fenugreek, and sage, thyme, parsley and coriander). But after the Crusades (1096 to 1291) the international exchange of goods became common and gradually Asian spices (pepper, nutmeg, cloves, and cardamom) became less expensive and more widely available. Spices were used to camouflage bad flavours, odours, and for their health benefits.

Cultivation of spices and herbs however was still largely controlled by the church during this period and they promoted this control through religious herb and spice feasts. Scholars have likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: It provided hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for those suffering from leprosy; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal. It also supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This church welfare system was funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and possessing large farmlands and estates.

The end of the tunnel

“There was no running water and knowledge of hygiene had almost become non-existent”

Disease is as old as mankind itself. Man has always tried to understand natural phenomena and attempted to give his own explanation to it. Although, the rich heritage of the Greeks had largely been ignored or forgotten by medieval Europe, in the early Arabist world the Hellenistic medical teachings and writings of Galen and Hippocrates were embraced and developed being translated first into Arabic and then into Hebrew. The medieval Islamic world produced some of the greatest medical thinkers in history. They made advances in surgery, built hospitals, and welcomed women into the medical profession. Al-Razi (865 to 925 AD) was a Persian physician (and chemist, alchemist and scholar) who was the first to distinguish measles from smallpox.

But in Europe the Middle Ages were a point in time when people were the most pious and God-fearing, the most dogged by evil and tormented by devils, demons and nightmares. Fear and worry dominated earthly life, plagues and disasters were seen as portents for the imminent end of the world. During the 11th century, however, life began to change. Agricultural innovations such as the heavy plough and three-field crop rotation continued to make farming more efficient and productive, so fewer farm workers were needed – but thanks to the expanded and improved food supply, the population grew. As a result, more and more people were drawn to towns and cities but the towns and cities were filthy, the streets open sewers; there was no running water and knowledge of hygiene had almost become non-existent. Dung, garbage and animal carcasses were thrown into rivers and ditches, poisoning the water and the neighbouring areas. So much so that in 1388 the English Parliament passed the first law requiring people to keep the streets and rivers clean. Meanwhile, the Crusades had expanded trade routes to the East and given Europeans a taste for imported goods such as wine, olive oil and luxurious textiles. As the commercial economy developed, port cities in particular thrived. By 1300, there were some 15 cities in Europe with a population of more than 50,000. Scientific thought grew by leaps and bounds and rational explanations were sought for every phenomenon. This situation gave rise to many discoveries in medicine too, as returning travellers brought back scientific medicine from Arabic texts. Hospitals were being built to care for the sick (eg St Bartholomew’s in London was opened in 1123 AD). A new era was being born in cities: the Renaissance.

Dr Stephen Mortlock is Pathology Manager at the Nuffield Health Guildford Hospital. He would like to thank the matron and all the staff at Nuffield Health, Guildford Hospital for their continued support. To see the article with full references, visit thebiomedicalscientist.net

Picture credit | Science Photo Library/Alamy/iStock

References

Forrest RD. (1982). ‘Development of wound therapy from the Dark Ages to the present.’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 75(4), 268-73.

Van Wyck HB. (1949) ‘Humanism and medicine; the decline of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Dark Ages.’ Univ Toronto Med J. 27(3):110-4.

Edriss, Hawa et al. (2017) ‘Islamic Medicine in the Middle Ages.’ The American Journal of the Medical Sciences , 354(3), 223 - 229

Horden P. (2009). ‘What's Wrong with Early Medieval Medicine?’ Social History of Medicine, 24(1), 5–25.

Hajar R. (2012). ‘The air of history: early medicine to Galen (part I).’ Heart views : the official journal of the Gulf Heart Association, 13(3), 120-8.

Hajar R. (2012). ‘The Air of History (Part II) Medicine in the Middle Ages.’ Heart views : the official journal of the Gulf Heart Association, 13(4), 158-62.

Berger D. (1999). ‘A brief history of medical diagnosis and the birth of the clinical laboratory. Part 1—Ancient times through the 19th century.’ MLO

Newman S. (2017) ‘Monasteries in the Middle Ages.’ The Finer Times.

Blainey G. (2011). ‘A Short History of Christianity.’ Penguin; pp 214-215.

Sabbatini S. (2005). ‘Attempts to fight paludism and malaria in the Middle Ages. Role of Benedictine and Cistercian monks in the rise of Monastic Medicine and in land reclamation during the Middle Ages.’ Le Infezioni in Medicina, 3, 196-207

Newfield, TP. (2017) “Malaria and Malaria-like Disease in the Early Middle Ages.” Early Medieval Europe 25, 3: 251–300.

Reiter P (2000). ‘From Shakespeare to Defoe: malaria in England in the Little Ice Age.’ Emerging infectious diseases, 6 (1), 1-11

Silvermann B. (2002). ‘Monastic Medicine: A Unique Dualism Between Natural Science and Spiritual Healing.’ Hopkins Undergraduate Research Journal. V1

Harrison, F., Roberts, A. E., Gabrilska, R., Rumbaugh, K. P., Lee, C., & Diggle, S. P. (2015). ‘A 1,000-Year-Old Antimicrobial Remedy with Antistaphylococcal Activity.’ Am Soc Biology, mBio 6(4), 1-7

Taylor GM, Murphy EM, Mendum TA, Pike AWG, Linscott B, Wu H, et al. (2018) ‘Leprosy at the edge of Europe—Biomolecular, isotopic and osteoarchaeological findings from medieval Ireland.’ PLoS ONE 13(12)

Reader R. (1974). ‘New evidence for the antiquity of leprosy in early Britain.’ J Archaeol Sci; 1: 205–207

Barberis, I., Bragazzi, N. L., Galluzzo, L., & Martini, M. (2017). ‘The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus.’ Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene, 58(1), E9-E12.

Moulis G & Martin-Blondel, G. (2012). ‘Scrofula, the king's evil.’ CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 184(9), 1061.

Naumova E. N. (2006). Mystery of seasonality: getting the rhythm of nature. Journal of public health policy, 27(1), 2-12.

Galdston I. (1954). The White Plague, Tuberculosis; Man and Society. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 42(1), 142–143.